whack-a-proc: catch hidden executables as they are injected

Nowadays it is fairly common for malware authors to use some form of process injection. The real malicious PE file (dll or exe) is hidden beneath one or more layers of wrappers which try to execute it as stealthly as possible, for example by injecting it in a seemingly harmless process. There is a wide variety of techniques to achieve process injection (check out this nice summary). For malware analysts the external layers of protection are just a nuance, and the most interesting code is in the final executable that is injected, so getting to it as quickly as possible is a primary goal. That is why I wanted to automate as much as possible the extraction procedure, for which I built a tool called whack-a-proc.

whack-a-proc

The idea behind whack-a-proc is fairly simple: we let the external layer decrypt/unpack its payload and inject it in a target process, and then just before its execution, we dump it from the process memory. This is actually one of the most common approaches used during manual analysis.

whack-a-proc is built on top of two components:

- APIhooklib - a library I have developed that allows to set inline hooks before and after the execution of target functions.

- pe-sieve - a powerful scanning tool created by hasherezade, which analyzes the memory of a target process in order fo find suspicious implants, such as rogue loaded modules, shellcode or hooks.

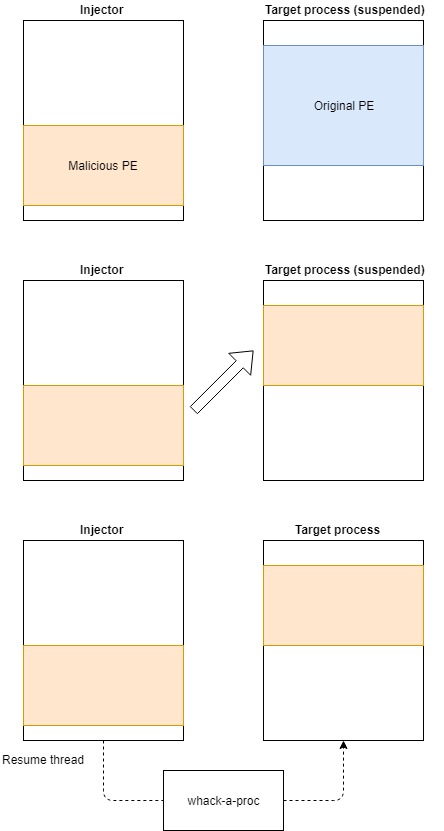

As an example we can take the case of process hollowing:

- The injector process creates a new suspended process with a harmless image (for example svchost.exe).

- It then unmaps the original image from the process memory and replaces it with the malicious PE file.

- Finally it resumes the main thread of the target process.

The new process appears to be a normal svchost.exe from the outside, while it is actually executing malicious code.

whack-a-proc puts itself in between point 2 and 3 by hooking a set of low level system APIs in order to scan the target process before its execution is resumed.

Lets see a couple of examples with real malware samples.

Practical cases

NOTE: The following examples use an old version based solely on a DLL.

Kronos

Sample: 2a550956263a22991c34f076f3160b49

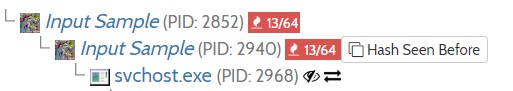

Kronos is an infamous banking trojan which first appeared in 2014. The sample we will look at is from 2017. This malware uses the already mentioned technique of process hollowing. If we take a look at the report of Hybrid Analysis, we can see that it creates a new process of itself, and then a new svchost process.

In this case the ability of whack-a-proc to monitor subprocesses as well becomes handy. Here it is in action:

In each folder pe-sieve writes the suspicious PE file if has found, together with a JSON report. In the first subprocess (2328) an executable of 290 KB is injected. Instead in the second one (3120) we get two different PE files. The first is the same as the previous, meaning that it is injected also in the svchost process; the second one, of only 21 KB, is actually the real svchost.exe image, which is still in the process memory because the malware does not bother unmapping it.

Osiris

Sample: 5e6764534b3a1e4d3abacc4810b6985d

Osiris is a newer version of Kronos that uses a more advanced injection technique known as process doppelganging. This technique makes use of transactions, a feature of NTFS that allows to group together a set of actions on the file system, and if any of those actions fails, a complete rollback occurs. The injector process creates a new transaction, inside of which it creates a new file containing the malicious payload. It then maps the file inside the target process and finally rolls back the transaction. In this way it appears as if the file has never existed, even though its content is still inside the process memory.

In this case we can see that the malware creates a new wermgr.exe process (3752) and it injects its payload in it. Once again the malicious second stage is dumped from memory.

About the project

At the moment whack-a-proc supports only the x86 architecture.

Binaries are available here.

If you want to check out the source code, you can find it on GitHub.