When monkeys create ransomwares

2016 has been a year full of ransomwares, and the trend doesn’t seem to change in the new year. Many “sophisticated” pieces of malware have been developed, from Locky, to Cerber, to the more recent Spora. But in the wild sometimes strange examples of wannabe-ransomware can appear, as the one we will look at here. Actually I’m writing this post just to make some fun of this script-kiddie masterpiece, so do not expect any obscure technique or advanced feature presented here.

Sample: Virustotal scan

General behavior

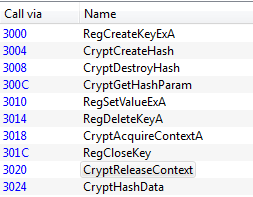

The sample is packed with UPX. After unpacking it, we can take a look at the import table to get a general understanding of how it works. Already something odd appears: usually ransomwares use the Windows CryptoAPI to perform the encryption, but in this case we can see only those regarding the hashing (CryptHashData etc.). This probably means that the encryption is performed by a custom function.

Moreover there seems to be no function to connect to the C&C server, which is rather strange because we would expect the ransomware to generate an encryption key “randomly” and then to send it to the C&C server. We can confirm the supposition by running the sample while capturing packets with Wireshark. Note that there is no anti-emulation technique, so this is the same behavior of a real victim.

Encryption mechanism

Lets take a look at how the malware encrypts the files of the victim.

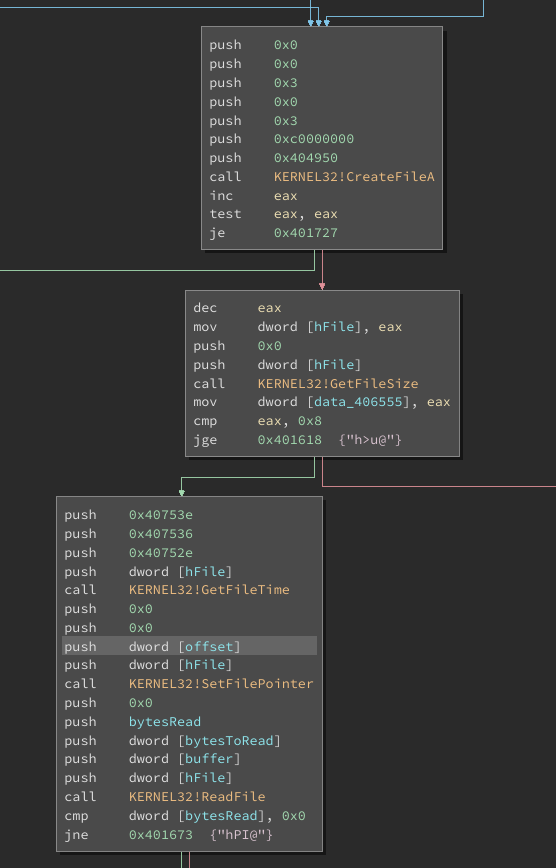

For each file, it starts reading at a specific offset, which is read from the resources (in this case 36 bytes). A single read operation is performed for a max size of 1735538 bytes. If the file is larger, the remainder is left unencrypted (LOL).

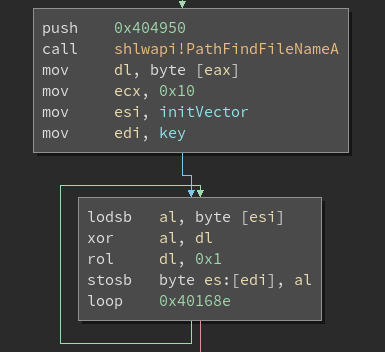

The encryption key is generated from an initialization vector that is read once again from a resource. Additionally, the generation routine uses the first character of the filename to create a “unique” key. Clever!

Encryption routine

The routine works on blocks of 8 bytes, each devided in two 32-bit integers.

encrypt_block(int n1, int n2, int keys[]) {

int i, s, t, N;

N = 0;

n1 = byteswap(n1); //bytewise reverse

n2 = byteswap(n2);

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

N += 0x9E3779B9;

s = n1 + (keys[1] + (n2 >> 5)) ^ (n2 + N) ^ (keys[0] + 16 * n2);

t = n2 + (keys[3] + (s >> 5)) ^ (s + N) ^ (keys[2] + 16 * s);

N += 0x9E3779B9;

n1 = s + (keys[1] + (t >> 5)) ^ (t + N) ^ (keys[0] + 16 * t);

t = t + (keys[3] + (n1 >> 5)) ^ (n1 + N) ^ (keys[2] + 16 * n1);

}

n1 = byteswap(n1);

n2 = byteswap(n2);

}

7/10 for the imagination, 2/10 for the result.

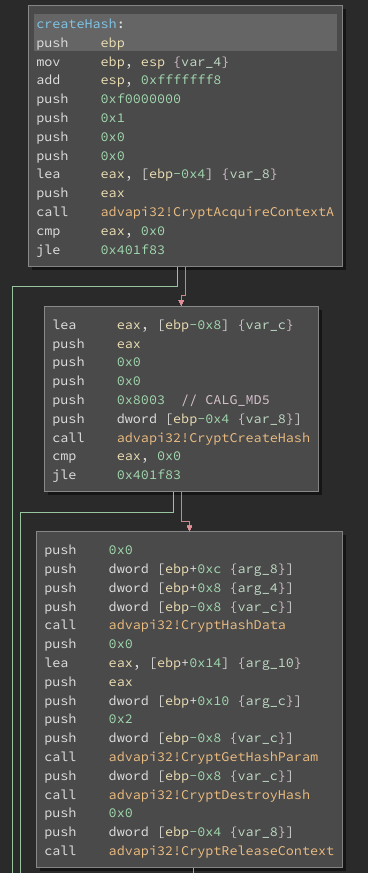

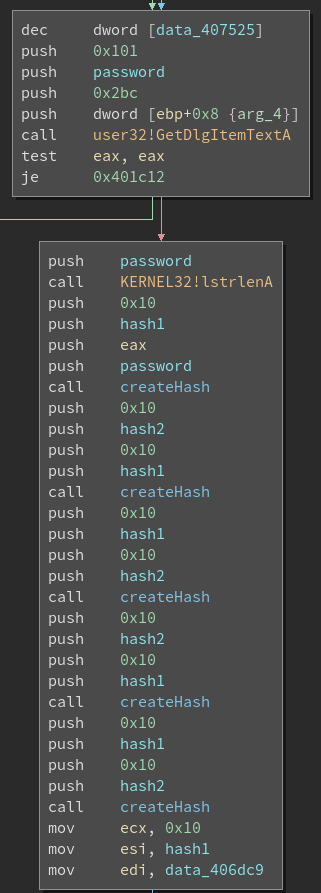

We know the key generation mechanism, we know the encryption routine, at this point creating a decrypter is just a programming exercise. But there is one last question left unanswered. If the ransomware does not communicate with a C&C server, what happens if a victim pays the ransom? Here come into play the hashing functions we found in the import table, which are used in the following function:

Basically this function computes the MD5 hash of the data passed in the parameters. But where is this function used?

The malware works also as the decrypter, and after the infection is completed it asks the victim for a password. The hash of the password (repeated 4 times, because why not?) is checked against an hardcoded value and only if they match the files are decrypted. This mechanism could actually be the ruin of the author, because it basically means that there is one single password for all the victims. Even if the ransomware had the most incredible of encryptions, we could just pay the ransom one time and then share the password between all the victims. All this effort for just one ransom, not really worth it.

Additional fun facts

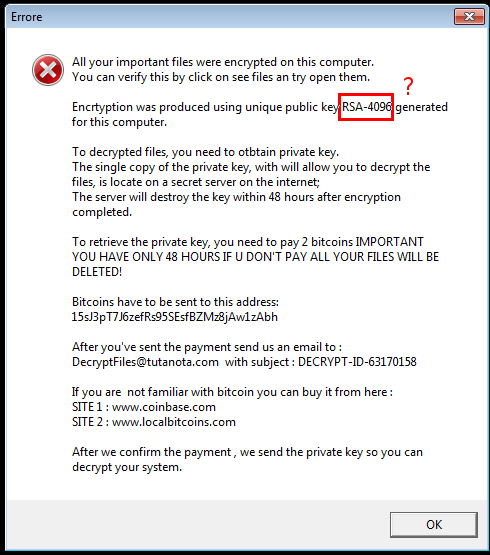

- This cute thing tries to be scary saying that it used RSA to encrypt the files. It also renames the encrypted files adding the extension .RSA-4096.

- If we submit a wrong password for more than 5 times, all files a destroyed. This feature is supposed to prevent the bruteforcing of the password. Unfortunately for the malware author, the counter is reset every time we close the program…