Deobfuscation of Bitpaymer API calls

In the plethora of bad ransomware that infests the internet these days, sometimes a “gem” stands out. This is the case of Bitpaymer. It targets companies, with ad-hoc samples for each victim, and it requires ransoms way above the average “spray-and-pray” ransomware. To attack such high-profile targets, it uses a set of features that you rarely find in ransomware: the use of ADSs, multiple layers of encryption and packing, and an elaborated system to hide calls to the Windows API. The focus of this post is the latter.

I had the chance to work on the first samples that appeared in the wild in July 2017 (thanks to demonslay335). Back then I stopped after unpacking the malware, as the obfuscation of API calls was quite daunting, and in the end, to determined how it encrypted the files of victims it was not strictly necessary to defeat it. Lately a new report has come up, with the attribution of Bitpaymer to the group behind Dridex. That reminded me of how the analysis remained incomplete, so here is how I completed the deobfuscation of API calls.

Before starting, if you are interested in how to unpack the malware and obtain its core, here is the link to a video by hasherezade on how to do it.

Call structure

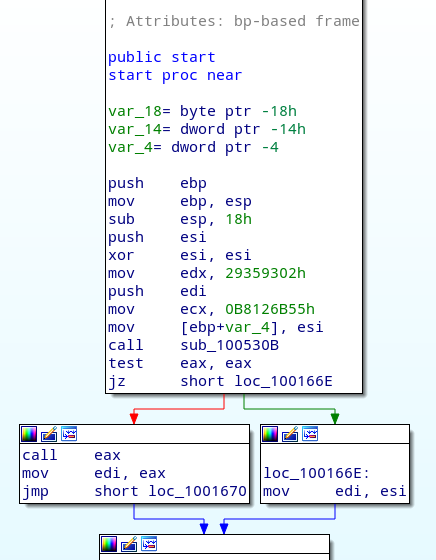

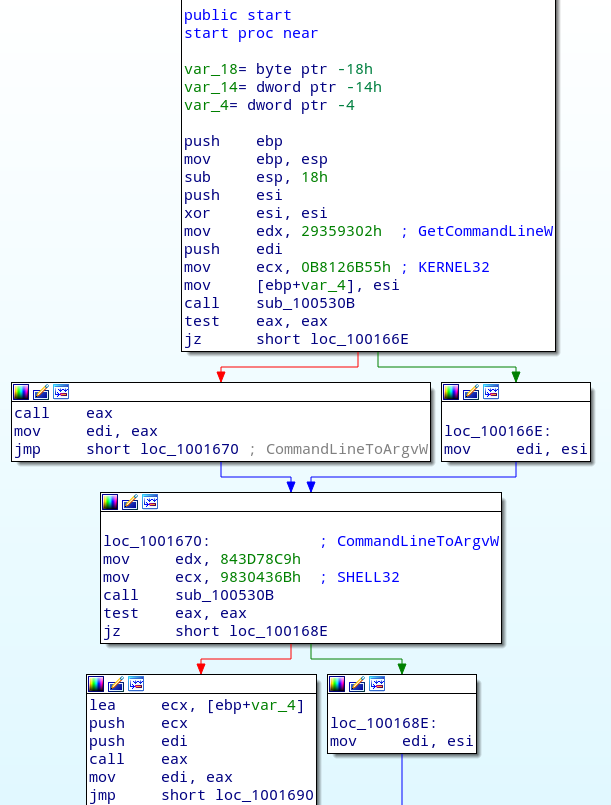

Once the core is loaded into IDA, we can see that already in the start function there are obfuscated calls. The general structure consist of:

- an immediate value in

ecx(HASH_1) - an immediate value in

edx(HASH_2) - a call to

sub_100530B(get_func_by_hash)

For example, the first call consists of HASH_1=0xB8126B55 and HASH_2=0x29359302. In this case the translated function is kernel32.GetCommandLineW, which is then called at 0xco01001668.

get_func_by_hash is called 148 times throughout the binary and it is the one and only function that translates the two 32-bit hashes into the corresponding function address.

Translation function

get_func_by_hash is quite a complex function, with multiple paths and loops. For example, right at the beginning we can see it has a specific behavior for two values of HASH_2, 0x88BB60D and 0x5153CEE2 (more on this later).

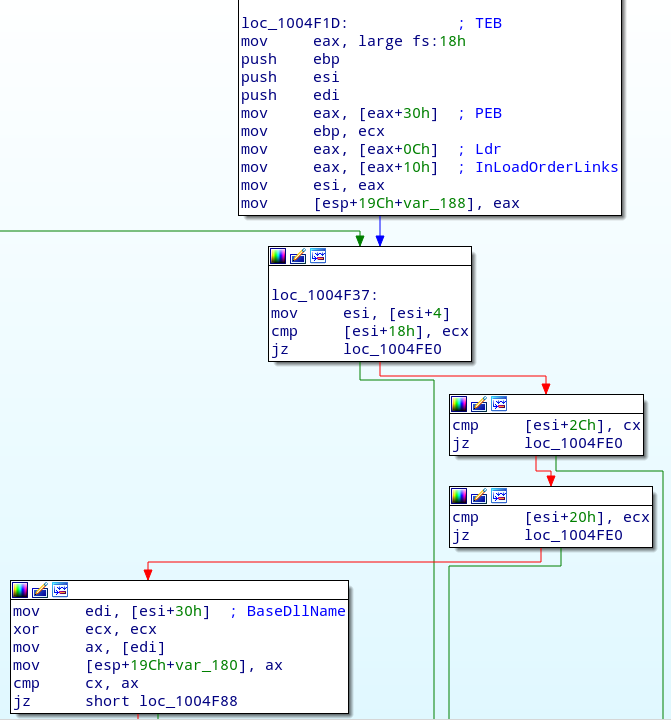

The interesting part starts at 0x010053A1, where the function sub_1004EB0 is called passing as parameter HASH_1. Once again we have an articulated function, so before diving into its code it is better to see it in action in a debugger. For the example mentioned above it returns the base address of kernel32.dll. This information leads us to two conclusions:

HASH_1refers to the DLL containing the required functionsub_1004EB0retrieves the DLL base address

This operation can be performed in multiples ways. Bitpaymer uses the “stealthiest” approach, in the sense that no API calls are needed. It retrieves the list of loaded modules from the PEB and walks through them until if finds the right one. This occurs at 0x01004F1D:

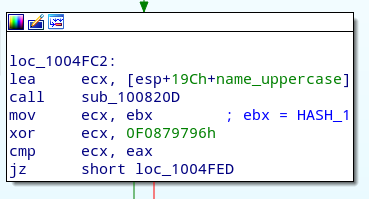

The extension is removed from the DLL name, and the result is converted to uppercase. At 0x01004FC2 we reach the core of the function, where the uppercase name is passed to sub_100820D, and its return value is compared against

HASH_1 ^ 0x0F0879796. If they match, the base address of the current module is returned.

Therefore, sub_100820D must be some sort of hashing function. Inside it we find a two interesting instructions:

shr eax, 1

xor eax, 0EDB88320h

These are tellers of the CRC32 algorithm. To sum up, HASH_1 is computed as:

HASH_1 = CRC32(uppercase_dll_name) ^ 0x0F0879796

The next step is to repeat the analysis for HASH_2, which is likely linked to the name of the function to be retrieved. Now, malware developers are humans, and humans tend to be lazy, so there is a considerable chance that they did not want to reimplement a completely different algorithm to hash the function names. It is worth a shot trying the same operation for the function name. We take once again the example of GetCommandLineW:

CRC32(“GetCommandLineW”) ^ 0x0F0879796 =

0xD9B20494 ^ 0x0F0879796 =

0x29359302

which is exactly the value of HASH_2. We now have the second piece of the puzzle:

HASH_2 = CRC32(function_name) ^ 0x0F0879796

With this information I wrote a simple Python script for IDA in order to show what functions are retrieved by the calls to get_func_by_hash. Here is an example of the result (the link to the script is at the end).

DLL and function tables

Repeating all this process every time an API function needs to be called is awful in terms of performance, therefore Bitpaymer uses a table to store the retrieved addresses. These are the involved data structures:

typedef struct _table_entry {

char *function_name;

int name_buf_size;

uint hash;

void *address;

} table_entry;

typedef struct _table_block {

table_entry te[16];

table_block *next;

} table_block;

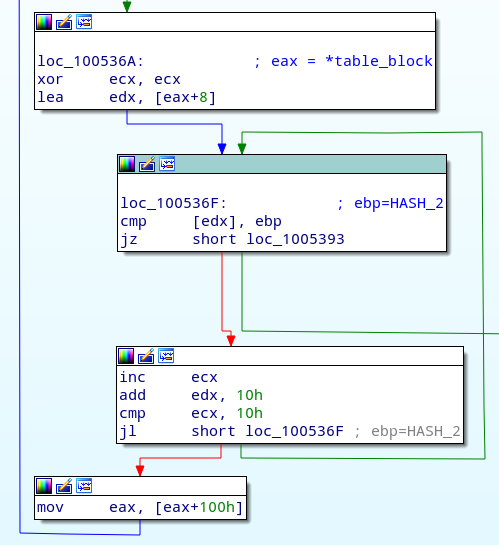

After the resolution of the first function, a table_block is allocated in the heap, together with 16 buffers of 0x40 bytes each, which will store the function names. Once all the 16 slots are filled and a new function is resolved, a new table_block is allocated and its address is stored in the next field of the last table_block. The result is a list of table_block structures which is walked for every call to get_func_by_hash.

The same data structures are used to store the base addresses of the DLLs. This is obviously an overkill considering that the malware needs only 5 modules.

The two special cases

We noticed that the values 0x88BB60D and 0x5153CEE2 of HASH_2 are managed in a different way, specifically their respective functions (RtlCreateHeap and RtlAllocateHeap) are stored in global variables. This comes with no surprise: since the tables are allocated in the heap, these function are needed before the tables even exist.

Additional information on the attribution

Just before writing this post I found this article about Dridex, published on September 29, 2016. The analysis of the API call obfuscation of that version of Dridex showed the same exact results I obtained with Bitpaymer, in terms of the resolution of API functions (with different constants but same algorithm) and in the data structures used to store the addresses. Unfortunately I was not able to retrieve the sample that was used in that article, so I cannot compare directly the two, but the similarities are clear. This is one more confirmation of the attribution of Bitpaymer to the Dridex group and it adds information on the development timeline of the two malware families.

Original sample: Hybrid Analysis

Core (not working by itself): Hybrid Analysis

IDAPython script: Github